Advertising and simulation

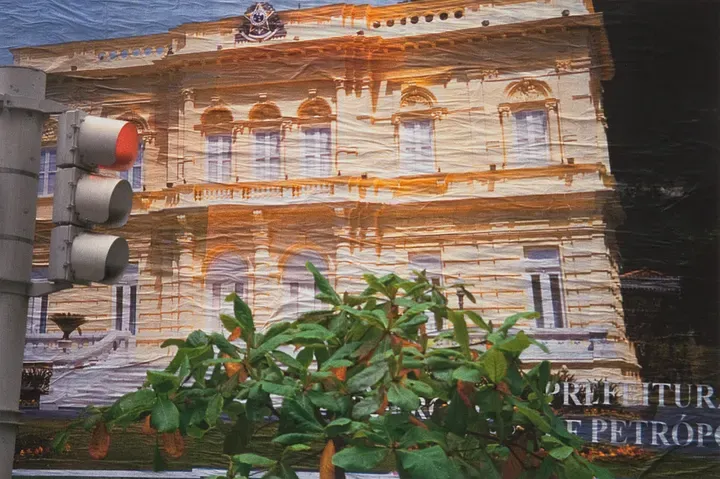

Jean Baudrillard took this photo of a street in Rio. A large sandstone building, grand, but not abnormal. A traffic light, forever fixed red. Ambiguous greenery. But the closer you look, the more the scene dissolves into illusion.

The building shimmers and ripples like a pond disturbed. The traffic light is plastinated and looms too close to the lens. The leaves of the tree are lit from all the wrong angles, as if by stage-lights. Baudrillard, through his tricks of composition and lighting, has arranged the idea of a streetscape, and not a streetscape itself. The scene looks, at first glance, to be real. But it vanishes at the touch.

What better introduction could there be to his grand theory of simulation?

In Simulations and Simulacrums, Baudrillard identified three orders of simulacrum. Each in turn increases in sophistication and subsumes the previous.

The first-order simulacrum is defined by its relation to something real. It can only be expressed in terms of that comparison, and no matter how sophisticated it becomes, how close a facsimile to the thing it replicates, it will always be inferior to it. He called this simulacrum a counterfeit, and gave as an example the clockwork automaton, that mimic of human behaviour in sprockets and gears. No matter how fine the mechanism, how advanced the movements, it can never stand alone. Its existence is predicated on the human it refers to.

The second order is one of production, where the simulacrum is defined in terms of its force: its output and effect on the world. It matters little that the robot arm on the assembly line looks nothing like the human it replaced. Its usefulness, the force it applies, is the same. The Waymo taxi gets you to your destination just the same as an Uber.

The relation to a specific real referent is broken. The simulacrum stands alone. But it still has a real use-value. Through its function it stays in touch with reality.

The third order, which permeates our lives so deeply it can be difficult to untangle and hold at arm’s length, is simulation. Here, the simulacrum can only be defined in terms of itself. There is no longer a ground truth, something real to which it refers.

The age of simulation thus begins with a liquidation of all referentials — worse: by their artificial resurrection in systems of signs

The prototypical example is capitalism: so deeply embedded it is in our society that we cannot posit any alternative except in opposition to it. The simulation has become the new real. As Fredric Jameson famously wrote, “it is easier to imagine an end to the world than an end to capitalism”. Of course, debates about any existing system must necessarily refer back to it, but capitalism is so entrenched that its alternatives are defined by it. Socialism is Capitalism-but-more-equitable, radical liberalism is Capitalism-but-more-free.

It’s hard to find a form of social relation untainted by simulation. Work, leisure, government, community — all are reduced to third-order simulacra.

There is no better example of the historical progression of simulation than advertising.

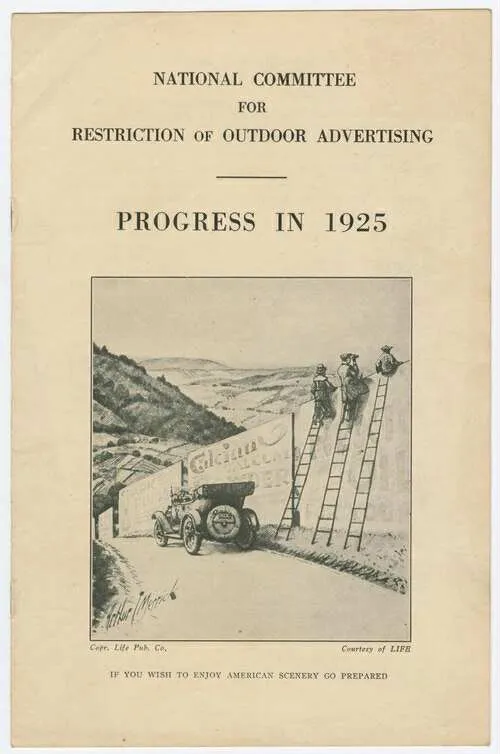

Something about older advertising appeals deeply to modern people — those hand-drawn posters where a wall of tight, emotional prose extols the virtues of a new product. The attraction cannot be explained by some inherent level of artistic or aesthetic quality, despite the often well-executed illustrations. Remember, contemporary observers hated their ads just as we hate our own.

And it’s not nostalgia. Whole generations have passed since the demise of this sort of traditional advertising.

Rather I would argue that these ads appeal because they are less developed simulacra. In fact, they are counterfeits of the first-order. They refer to a specific real: the salesman, breathlessly travelling door to door to deliver his pitch. The pitch, too, differs in its specificity. It drips with facts and figures. This is so refreshing to us because it is so foreign. In a life defined by simulation, a life unmoored from the real, a return to counterfeit feels strangely honest.

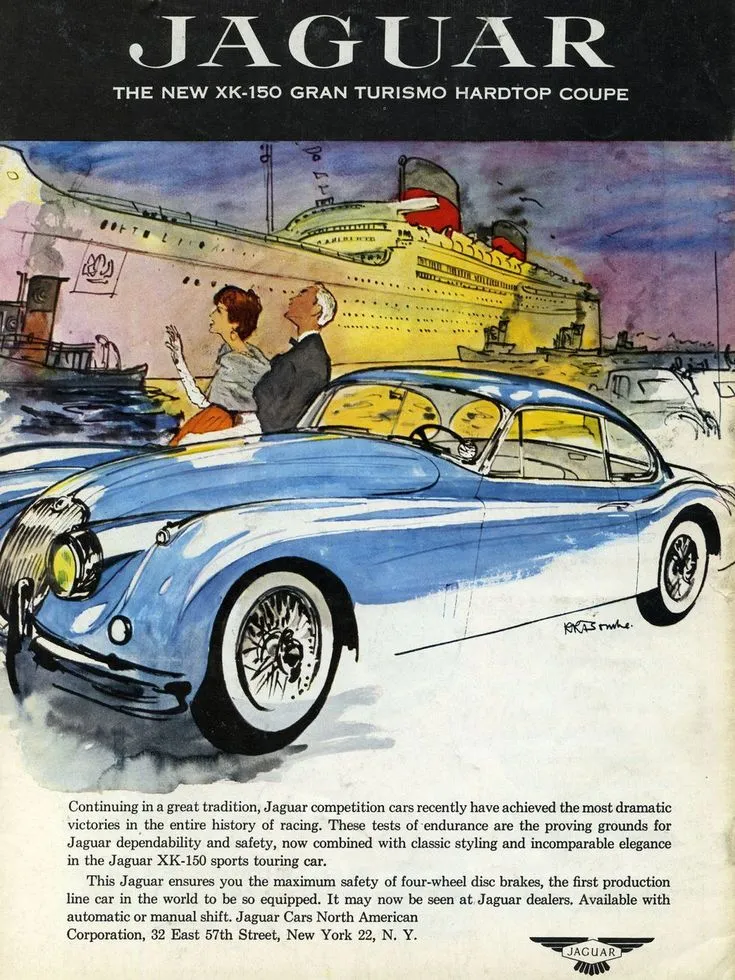

Compare the print ads for Jaguar to this 2024 abomination. There is not an iota of real in the whole thing. It refers to nothing. It is completely defined by itself, a perfect unattached simulation. This is modern advertising: a third-order simulacrum.1

An advertising of simulation is advertising in its final and most parasitical form. It is psychological violence wrought upon humanity.

A digression: What about second-order advertising? Before the Kardashians we kept up with the Joneses: the nuclear family as defined by its use-value. The archetypal doting mother, hard-working father and two-and-a-half blond children in the identical houses, manicured inside and out. All of the families technically interchangeable, like Baudrillard’s robot. One mother is as good as any other mother, just so long as she keeps up.

Baudrillard considered this order something of a blip in history, and it was a blip in advertising, too. The Joneses are dead. An advertising of simulation is about you.

You are news, you are the social, the event is you, you are involved… A turnabout of affairs by which it becomes impossible to locate an instance of the model, of power, of the gaze, of the medium itself, since you are always already on the other side.

Under simulation, a person can only be defined in terms of their difference to that simulation. The message of advertising must now be “Express yourself — define yourself in opposition to the simulation”.

The push to self-expression is often obvious. But isn’t the message exactly the same in “counter-cultural” advertising? Set yourself apart. Check out from the rat race. Express yourself, through your lack of self-expression.

Is it an accident that the slogan in that new Jaguar ad is “Copy nothing”?

There is no possible consumer choice that does not define itself in terms of the simulation. This is Baudrillard’s point. By expressing yourself, you prove your difference by participating in the simulation, just the same as everyone else.

Advertising is everywhere. It permeates our very existence. And, what’s more, it has assimilated all other forms of media.

I overheard a conversation on the light rail yesterday. A young woman, fresh out of university, explained her job at the Daily Mail. She works in Breaking News, which, as she described it, consists of writing as quickly as possible descriptions of every domestic violence incident in Australia, publishing them, then watching the analytics roll in. If the view count proves that the crime is sufficiently horrific, and therefore sufficiently revenue-generating, she scrubs all mentions of Australia from the title and posts it again, this time to the entire world.

So it is that journalism is indistinguishable from advertising. It, too, refers only to itself. Its only role is to perpetuate an endless “conversation”. The imperative is: Stay informed, have your say, don’t fall behind, don’t miss a trick. Discussion, conversation, debate, opinion poll, vox pop. There is no longer a real behind this conversation. It perpetuates itself, generates its own heat-energy from the voices of a billion hot takes, and in the process generates untold advertising revenue.

Capital, which is immoral and unscrupulous, can only function behind a moral superstructure, and whoever regenerates this public morality (by indignation, denunciation, etc.) spontaneously furthers the order of capital.

Advertising and journalism provide that superstructure. They enforce their own twisted form of morality. Advertising controls what is good and what is aspirational: possession, self-expression, high status. Journalism controls what is bad: being insufficiently skilled at playing by the rules of the simulation.

If only there were shadowy cabals of advertising execs and journalists in mahogany-panelled offices somewhere, planning this all out over a Scotch. The world lacks a locus of rage.

Capital doesn’t give a damn about the idea of the contract which is imputed to it — it is a monstrous, unprincipled undertaking, nothing more.

The moral superstructure is generated by its subjects. When we read a clickbait article, when we buy a “Season 7” White Fox hoodie, we do our part to define the simulation. To even reject the simulation is to prop up its existence. It only exists because you reject it. There is, after all, nothing real behind it at all.

Footnotes

-

The tired idea comes up again and again that ads like these are deliberately bad, and designed to stir up controversy. Talk to someone in advertising and you’ll realise the truth is worse. They really, really believe in this shit. ↩